The joint venture rules that tie foreign asset managers to their Chinese counterparts have recently changed, leaving the future uncertain for many. Stefanie Eschenbacher investigates.

The joint venture rules that tie foreign asset managers to their Chinese counterparts have recently changed, leaving the future uncertain for many. Stefanie Eschenbacher investigates.

Shanghai’s parks are famous – not so much for their greenery but for their informal marriage markets held on Saturday and Sunday afternoons.

With handwritten profiles – stating age, education, salary and whether they own a car or an apartment – hundreds of parents seek the perfect match for their children there.

China will have an estimated 24 million bachelors by 2020 as a result of gender imbalances. No wonder competition is fierce.

In corporate Shanghai, however, there are doubts over lifelong attachments. The joint venture rules that tie foreign asset managers to their Chinese counterparts have changed. Further changes are expected.

Domestic shareholders no longer need a foreign partner to own a controlling stake – 51% or more – in domestic joint venture fund management companies.

Ivan Shi, senior adviser at Z-Ben Advisors, a Shanghai-based consultancy, says this has raised suggestions that the joint venture model is diminishing.

Previously, in a joint venture, domestic companies could own no more than 49%. If they wanted to own 51% or more, they had to bring in a foreign partner.

In a separate move by a regulator, three Taiwanese companies have also been promised controlling stakes of up to 51%.

Sinopac Securities, the brokerage arm of SinoPac Financial Holdings, in Taiwan, is in the process of forming a joint venture with Xiamen JinChai Investment, a subsidiary of the state-owned Xiamen Jinyan Investment Group.

The deal is pending regulatory approval. If it goes ahead, the company will be able to hold up to 51% in the joint venture.

Hector Xu, deputy general manager at Aegon Industrial Fund Management, says most joint ventures lag behind their domestic peers.

Xu reckons it is no coincidence that the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has chosen to open the market towards Taiwanese asset managers first.

“Why Taiwan? It is not as competitive as Hong Kong,” Xu says. “Taiwan is the first step, then Hong Kong and, eventually, the rest of the world.”

With restrictions loosening, he predicts as many as half of the joint ventures will break up.

Qing Yu, chief inspector and chief operation officer at Axa SPDB Investment Managers, shares this line. He predicts as many as half the foreigners will be kicked out. “The future of a lot of businesses is mixed.”

Cross-cultural joint ventures are among the most difficult to navigate for both sides. Xu says cultural differences are the main reasons joint ventures struggle, adding that battles over who controls the company make the business unstable.

Investment style often varies significantly. Westerners with renminbi qualified foreign institutional investor (RQFII) quotas tend to focus on banks and other blue chips when they buy A-Shares.

Whereas Chinese asset managers, he adds, invest to make a “quick profit”, even if this means a large portfolio turnover.

Xu and Yu agree that joint ventures, where the investment staff is domestic, have performed better, with the exception of qualified domestic institutional investor (QDII) schemes.

Cheng Liao, director, Asia business development, at Axa Investment Managers Japan, says that locals tend to doubt the investment expertise of foreigners when it comes to their own market.

Liao says problems arise when foreigners try to impose their investment style and investment philosophy on the local partners.

Chengsen Yeh, director, financial services, at Ernst & Young, says the Chinese market is still seen as promising by foreign asset managers.

Though in recent years, problems with the joint venture model in general have become more apparent.

“Most foreigners have little to say about the way business is done,” Yeh says.

Many joint ventures have failed to endure; investment restrictions loosened, foreigners gained experience in China and the local asset management industry is maturing.

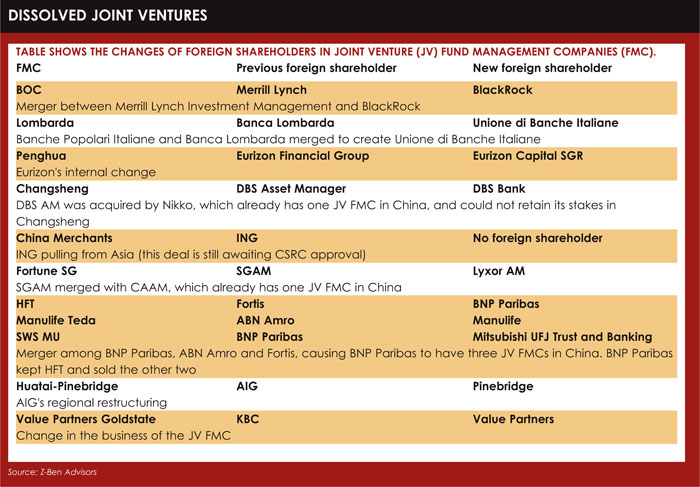

Eleven fund management joint ventures have been dissolved, Shi says, but just one because its business struggled in China. Most of the others were dissolved because of changes within the global institutions (see table). Some of those were caused by non-compliance in China because one foreign institution is only allowed to have one joint venture fund management company.

Although Shi does not deny that there are cultural clashes between Chinese and foreign shareholders, he says the real issue is usually corporate governance. He says both domestic and joint venture fund management companies have had such issues, resulting in political struggles among shareholders, high staff turnover and an instable corporate structure. “The CSRC has recognised this and started to address it.”

There are proposals on how fund management companies should construct their board of directors, give more seats to minority stakeholders and create a management structure where different parties can discuss their strategy.

Most joint ventures are in the mid-tier group of fund management companies, where it is difficult for them to compete with larger ones. Half of the top ten fund management companies are now joint ventures. China Asset Management Company, where Power Corp owns 10%, and Harvest Fund Management, where Deutsche Bank owns

30%, were leaders before they became joint ventures.

The other three top joint ventures are all bank-backed fund management companies that have climbed quickly in the past year, thanks to the support in new product offerings.

“Generally speaking, the joint venture structure did not have a lot of contribution to the ascendance of these firms in market share competition, or is not the primary reason here,” Shi adds.

Several big Chinese fund management companies have already established subsidiaries in Hong Kong. While they focus on investing in China, it is likely that they will try to become regional specialists for the Asia Pacific region.

“They will need investment processes only a global institution can provide,” Shi says. “Although we have this change in regulation, Z-Ben believes the joint-venture model is important for doing business here. It is the most mature platform for foreign institutions to take part in China.”

Shi is also more tentative when it comes to China’s recent pledge to allow Taiwanese companies to own a majority stake in a joint venture. “Taiwan is only a special case here,”

he says.

The financial industry in China, including fund management companies, is restricted for foreign investment according to regulation from the National Development and Reform commission and the Ministry of Commerce. The cap on foreign ownership is 49%.

The financial industry in China, including fund management companies, is restricted for foreign investment according to regulation from the National Development and Reform commission and the Ministry of Commerce. The cap on foreign ownership is 49%.

Although the CSRC probably advocates further the opening up of the mutual fund industry to foreign investment, Shi says any chance in that respect will still need to wait for a change in higher rules from those government entities. “The reason for Taiwan being a special case is that Beijing has special economic co-operation agreements with Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau,” he adds.

China’s economic relationship with Hong Kong is defined by the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangements (CEPA). China’s alliance with Taiwan is through the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA). The CSRC granted Taiwanese companies a special treatment under the ECFA framework.

“The same special treatment is possible in the future for Hong Kong institutions under the CEPA framework,” says Shi.

In the past couple of years, China and Hong Kong have signed several supplement agreements for CEPA. The RQFII scheme is just one of them.

The CSRC has further deregulated the market in recent months, meaning that fund management companies are able to expand beyond the mutual fund space into alternatives.

Cross-border investment schemes can be one way for Chinese and foreign asset managers to make it work.

The QDII scheme allows Chinese asset managers to raise assets in China and then invest them overseas. Whereas the qualified foreign institutional investor (QFII) scheme allows foreign investors to buy A-shares listed in Shanghai or Shenzhen.

“It took so long for Chinese asset managers to realise that QFII and QDII is their future,” Yeh says.

At Aegon Industrial Fund Management, Xu says both parties have been working together successfully. The team in Shanghai manages two sets of QFII quota, that of Aegon and that of a former Aegon company in Taiwan.

Xu says he envisages establishing a QDII fund and perhaps expanding into other business areas, such as wealth management. “We will probably provide some value-added services and other innovative products,” he says. “It is a hard time for mutual fund companies in China because stockmarket performance has not been good.”

Competition increases as more asset managers are entering the market and he says everyone needs to make a choice.

While Axa SPDB Investment Managers does not have a QDII fund, Liao says there is a trend towards such schemes.

GROWTH STORY

There are other changes, too, in the Chinese asset management industry. The quasi-monopoly of banks is starting to crumble as foreign banks and independent financial advisers are seeking approval to sell mutual funds to the public.

“The CSRC has enlarged a lot of distribution channels, which is good news,” says Yu. “There is a fund industry joke that the bank is the boss of your company because the banks control many customers of fund management companies.”

There are plans for Axa SPDB Investment Managers to broaden its services to become more tailored for targeting high-net-worth-individuals and to win segregated mandates.

Yu says the recent move of Chinese fund management companies to Hong Kong is “just the beginning” of the expansion strategy. Europe and, eventually, the US will follow.

His team plans to establish a subsidiary which can engage in the asset management of segregated accounts, mutual fund sales and other business, as licensed by the CSRC.

“When the subsidiary will be established depends on the actual business development of our company and the approval of shareholders and the CSRC,” he says. Yu adds that once the subsidiary is established, it could make full use of the resources of both joint venture partners.

Liao says the priority is to ensure the joint venture is a market competitor with synergy from shareholders and local experts.

Joint ventures are a marriage of convenience. Their future will depend on whether there is a more convenient way for local or foreign fund management companies to participate in the China growth story.

©2013 funds global asia

At times like these, HSBC Asset Management easily pivots towards emerging markets.

At times like these, HSBC Asset Management easily pivots towards emerging markets. A comprehensive, cost-effective, and transparent currency overlay hedging solution is crucial to mitigate FX exposure risks in the complex landscapes of Japan and China's FX markets, explains Hans Jacob Feder, PhD, global head of FX services at MUFG Investor Services.

A comprehensive, cost-effective, and transparent currency overlay hedging solution is crucial to mitigate FX exposure risks in the complex landscapes of Japan and China's FX markets, explains Hans Jacob Feder, PhD, global head of FX services at MUFG Investor Services. Contradictory market sentiments from commentators have impeded the decision-making powers of the first wave of AI-powered ETFs, says Alvin Chia of Northern Trust Asset Servicing.

Contradictory market sentiments from commentators have impeded the decision-making powers of the first wave of AI-powered ETFs, says Alvin Chia of Northern Trust Asset Servicing. The world is transitioning from an era of commodity abundance to one of undersupply. Ben Ross and Tyler Rosenlicht of Cohen & Steers believe this shift may result in significant returns for commodities and resource producers over the next decade.

The world is transitioning from an era of commodity abundance to one of undersupply. Ben Ross and Tyler Rosenlicht of Cohen & Steers believe this shift may result in significant returns for commodities and resource producers over the next decade. Ross Dilkes, fixed income portfolio manager at Wellington Management, examines the opportunities and risks for bond investors presented by the region’s decarbonisation agenda.

Ross Dilkes, fixed income portfolio manager at Wellington Management, examines the opportunities and risks for bond investors presented by the region’s decarbonisation agenda. Shareholders in Japan no longer accept below-par corporate governance standards. Changes are taking place, but there are still areas for improvement, says Tetsuro Takase at SuMi Trust.

Shareholders in Japan no longer accept below-par corporate governance standards. Changes are taking place, but there are still areas for improvement, says Tetsuro Takase at SuMi Trust.